Paul Bernhardt | The Reflex

March 24 – April 30, 2016

Opening reception | Thursday, March 24 at 7 pm

Artist Talk | Saturday, April 16 at 2 pm

Alberta artist Paul Bernhardt deals with technological cultures in his paintings and installation. The Reflex draws on imagery of video games and obsolete workplace punch-clocks, creating paintings that are themselves captured in a surveillance system of mirrors within the gallery. The violence and control implicit in our technological society, and suggestions of falseness, mock the images in fractured reflections—but from the right point, the glowing image is readable, if distorted.

The machine comes to life

Paul Bernhardt’s The Reflex, by Andrew Buszchak

The work lay like a dormant machine, dependent on a certain combination of lighting conditions and the precise positioning of the eye of the beholder. It targets individual viewers, taking them out one at a time. The work is actually smaller than the sum of its parts. It projects an exhibition of paintings as a cloaking device so that it may pursue its real purpose more efficiently.

As one enters the ProjEx room, there are three large, monochromatic green paintings of slightly loose handling hung together on the south wall. With varying approaches to iconography, they each represent a distinct period of western consumer electronic technology, reading from left to right in brisk chronological order: on the left, a “nuclear family” watching television, possibly circa 1950’s; next, a “10-point” alien from the video game Space Invaders (1978); finally, what seems like it could be a photograph of a field obscured by clouds, taken on a smartphone from an airplane window.

On the adjacent north wall, a much smaller, monochromatic grey painting hangs on its own, and is further distinguished by an ornate, gold-leafed (or possibly gold spray-painted) frame. The image it bears is a painterly rendering of a video still taken from the targeting system of an apparent “smart bomb” attack on a solitary pick-up truck parked next to a structure.

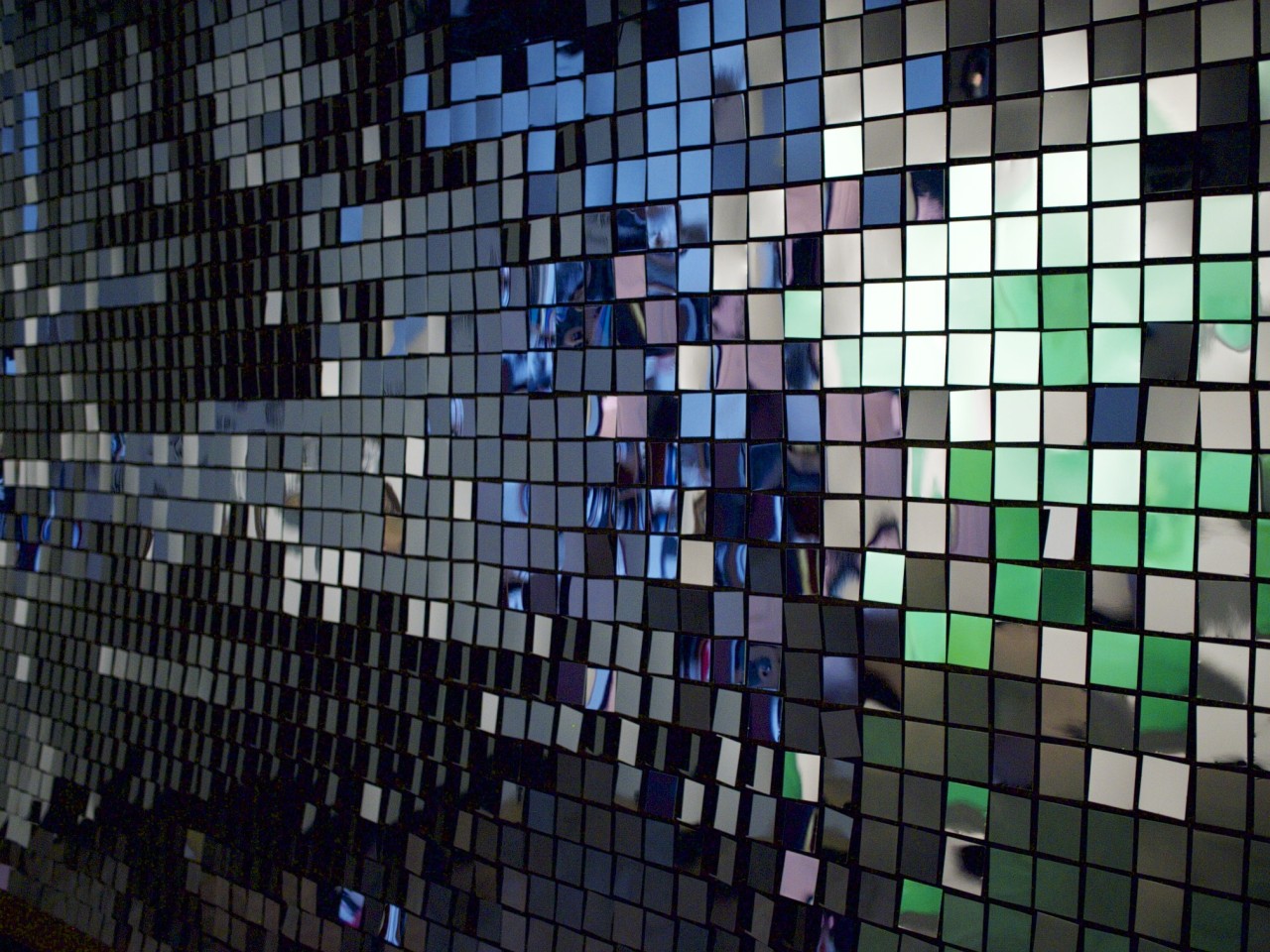

Marked on the floor, approximately one meter from the south wall, in front of the center of the three green paintings, is a green box styled after the targeting reticle at the centre of the grey painting. Directly across from this spot, on the north wall of the space, is a massive array of individually positioned squares of aluminum, polished to a mirror-finish.

With a viewer looking at the array of mirrors from the targeting reticle marked on the floor, the dormant machine comes to life; a heavily distorted or “pixelated” secondary representation of the painted representation of the “smart bomb” video still begins to coalesce. It is a peculiar inclination to think of the mirror array in terms of pixels because the mirrors are not pixels; that is, not tiny emissions of light from a computer monitor. However, by direct, low-tech means they do present as a matrix of discreet spots of either light or “not light” and so reproduce an appearance similar to that of low-resolution digital images.

Over the last five or so decades, electronic technology and media has proven its fidelity in documenting and disseminating news of events in the world, both of intimate and mass scale, and of private and public interest. Conversely, due to its relatively broad accessibility, electronic technology continues to prove endlessly malleable, therefore requiring an ever more sophisticated ability to read the products of such media. Furthermore, its ubiquity engenders an increasingly jaded disposition in the user; people come to expect diminishing joy, satisfaction or excitement from life, while their tolerance for boredom, inconvenience and struggle is sapped.

When The Reflex has a viewer in its sights, it reflects (more figuratively than literally, despite the mirrors) the immense, unrelenting, unidirectional pressure that technological progress puts on the lives of the people who accept it, whether actively or not, as the basis for their reality. When this machine locks-on to a viewer, it reveals the destruction that highly technologized people have become accustomed to and have come to expect of the world around them.

-

Andrew Buszchak is an interdisciplinary artist working most lately in video, print, sculpture and exchange. He was recently named among the twenty-five Alberta-based artists selected to participate in the 2017 Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art. In 2015, he contributed recent work to the Art Gallery of Alberta’s exhibition Do It Yourself: Collectivity and Collaboration in Edmonton and his durational office light installation, “Beacon”, was produced for Edmonton’s inaugural Nuit Blanche.