Shan Kelley | Clean, Fit and Decease Free

December 4, 2015 – January 16, 2016

Opening reception | Friday, December 4 at 7 pm

Day Without Art Film Screening: Tuesday, December 1 at 7:00 pm

Since being diagnosed HIV+, Shan Kelley’s mixed-media work has focussed on the feeling of exposure, of oppressive surveillance as it questions of sexuality and private life become seemingly-fair game for moral scrutiny and study. Kelley’s images answer the demand for explanation given to a positive person with a similar force, through mixed-media work that embeds his poz body in the gallery.

Day Without Art Film Screening: Join Shan Kelley on Tuesday, December 1, for two short films and a discussion.

Radiant Presence (5 min) is a digital slideshow with images from the Visual AIDS' Artist+Registry, the largest database of works by artists with HIV/AIDS. RADIANT PRESENCE features artwork by artists living with HIV/AIDS and those who are no longer with us. The artwork is interspersed with current statistics and information about HIV/AIDS today.

Consent (22 min), a documentary film produced by the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network and Goldelox Productions. In their own words, eight women — leading feminist scholars, attorneys and women living with HIV — shine a light on the problems of using sexual assault law to prosecute alleged non-disclosure of HIV. Does the legal concept of consent, intended to protect women’s sexual autonomy, in fact increase their risk of violence and discrimination when used to criminalize HIV?

The artist tells you who they are and who they aren't: Shan Kelley, and disclosure

Shan Kelley is not his father or his child, yet each pictured in bundled frailty they are together a trinity of familiarity, their near deathness, their near birthness a reminder that life is circular. We are connected.

Shan Kelley is not Casper the Friendly Ghost, that is to say he has not been rendered dead. Although he has been close, and is in fact friendly.

And Shan Kelley is not Mr. Clean, at least not by the standards of contemporary hook-up culture which demands subjects be clean, fit and disease free. But he is fit 😉.

Instead, Kelley is an artist, family member, and sexual being, yours for the peeking, his flesh, sex, HIV+ status, citizenship and feelings detectable for viewing.

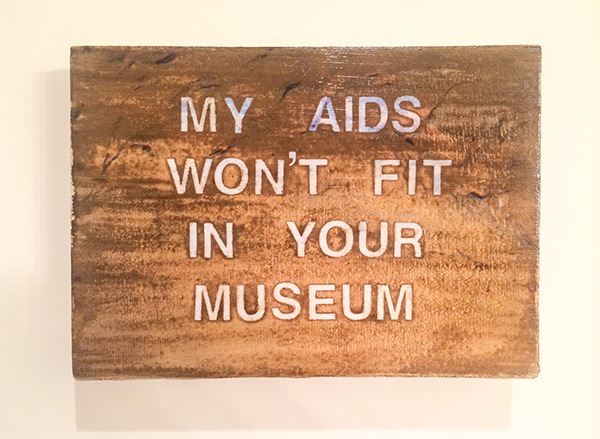

Through exhibitionism, obfuscation, foil, and your voyeurism Kelley is giving us a lot of himself, and yet, Clean, Fit and Decease Free is not all of him, a fact he spells out for us in small-scale oil paintings that read: “My AIDS Won’t Fit In Your Museum”, “Raised Skin Where A Wound Once Healed”, and “I Fill Of You Just To Be Myself Again”. This shell game of the self is a learned behavior for survival.

Like artists Glenn Ligon and Divya Mehra, Kelley uses text as material, exploring cultural norms and personal issues. There is a current cultural obsession with cataloging the history of HIV in public with little concern about the administrative and state induced wounds exasperating the reality of living with HIV in public.

In 2012 the Supreme Court of Canada decided that people’s status living with HIV was more important than their humanity. The Court released a decision stating people living with HIV must disclose their status before engaging in sexual relations that may pose “significant risk”. The Court did not stipulate what constitutes “significant risk” nor did they factor in the complex realities of how sex is actually negotiated. In response, AIDS Action Now, a Canadian AIDS Activist group, came out against the criminalization of HIV nondisclosure: “The ‘law and order’ approach does virtually nothing to stop HIV transmission, stigmatizes people living with and at risk of HIV, and is undermining proven HIV prevention strategies and programs.”

From 1989 to 2012, 140 people have been criminally charged with HIV non disclosure in Canada, with over half of the cases resulting in convictions and 90% of people convicted going to jail. In her article “Canada’s Vicious HIV Laws”, Sarah Schulman summarizes, “HIV criminalization is denunciation-based.” It pits people not living with HIV against people living with HIV, with people living with HIV at a disadvantage.

In response to the ways in which criminalization acts as divisive for people living with HIV, Kelley responds with art. “Order” is a Canadian flag mailed around to Canadians living with HIV on to which they would ejaculate. It could be read as a “fuck you” to the state, while at the same time be understood as an act of solidarity and world-building. The Maple Leaf becomes the bull’s eye instead of people living with HIV, a reversal with erotic motivations.

Individual works like “Order”, as well as “Count Me Out” and “Rebound” illustrate how while Kelley’s work is not solely about HIV criminalization—or HIV for that matter—it is focused on concerns associated with HIV: vulnerability, traceability, sexuality, location, and the limits of the physical and social body.

Kelley is negotiating vulnerabilities and limits as means of participation, disclosure and self protection in a country where jail—and premature death—hover over people living with HIV not like a friendly ghost but an anvil. He wants to let us in, there is an argument that he has to let us in, but also he needs to protect his humanity from state forces that position him primarily as a weaponized risk.

His work exists in concert with artists Jessica Whitbread and Vincent Chevalier whose practice also often includes their HIV status. Through her “No Pants No Problem” dance parties and “Tea Time” gatherings for women living with HIV, Whitbread is carving out fun, nurturing and communicative space where her HIV status is not exceptional or oppositional, rather it is unifying. In works like “So... when did you figure out that you had AIDS?”, “AIDS ART”, and “Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me” Chevalier is experimenting with what distances can be made between HIV, status, art, and the individual. In a panel discussion about becoming well known due to his positive status, Chevalier stated that creating an online public persona including his status is a strategy. As people engaged with the persona he has the psychic space to carve out privacy in which he can live through the multiplicity of his experiences.

This negotiation of the self, status and creation is occurring at an interesting time in the world of AIDS. PrEP, the little blue HIV prevention pill not yet available in Canada is remaking the present and future state of AIDS, meanwhile there is a growing interest in AIDS of the past. It’s hard to find an activist across the US and Canada who hasn’t seen the film, “How To Survive a Plague” and “United in Anger” or haven’t been part of a formal or informal inter-generational gathering about the “early days” of the virus. This look back via storytelling and media is what I refer to as the cultural AIDS Crisis Revisitation. It comes out of and draws to a close something the Second Silence, a period of 12 years in which the creation and dissemination of AIDS related media went into decline while new cases of HIV were occurring alongside medical and political advancements. The Second Silence, coming nearly a decade after the lack of robust governmental action during the “first five years” of the virus, begins in 1996 with the launch of life saving medication for people living with HIV. The Second Silence ends in 2008 with the release of the Swiss Consensus which confirms that for people living with HIV on treatment that works for them their viral load can become so low it is undetectable, meaning the virus is rendered sexually non-infectious.

Kelley, like myself (as well as Chevalier and Whitbread, and Mehra for that matter) came into teenage-hood and young adulthood during the Second Silence. We went from being inundated with AIDS prevention messaging as children to being left to make sense of the virus in a cultural vacuum. For people who sero-converted during this time, the Silence was that much more heady. In researching the virus on one’s own, one encountered images and stories of community mobilization and support that within the Silence was privatized. Gone were weekly meetings in community centers where protests were planned and debated. In their place large social service waiting rooms popped up, where everyone is living with HIV but no one is talking about it.

For many of us, regardless of our status, AIDS went from explicit to implicit. This has importance in relation to Kelley’s work. One may wish to dive into the subtle and unsubtle ways HIV appears in the art, is the art. But more helpful would be to understand that coming of age in the Second Silence, and now living with HIV in a country where it is criminalized, everything is AIDS. Every day is World AIDS Day.

To exist as a being, a being with emotions, urges, desires needs and HIV, Kelley constructs and deconstructs ideas of the self, maintaining an instability to his identity carving out a spaciousness required to be human, while broadcasting a stable idea of himself as associated with fallibility, humor, the inhumane, death and risk.

—Theodore Kerr

Theodore (Ted) Kerr is a Canadian born, Brooklyn based writer and organizer. He was the programs manager at Visual AIDS and is currently doing his graduate work at Union Theological Seminary. Shan Kelley is an Edmonton born, Montréal based artist and health policy advocate. He has a mixed practice that sits amidst the slippage of intersections between art and activism. Shan Kelley is an Edmonton-born, Montréal-based artist and health-policy advocate. He has a mixed practice that sits amidst the slippage of intersections between art and activism.