Luther Konadu | Figure as Index

February 23 - March 31, 2018

Artist Talk: Friday, February 23 at 6 pm

Opening reception for members and guests: Friday, February 23

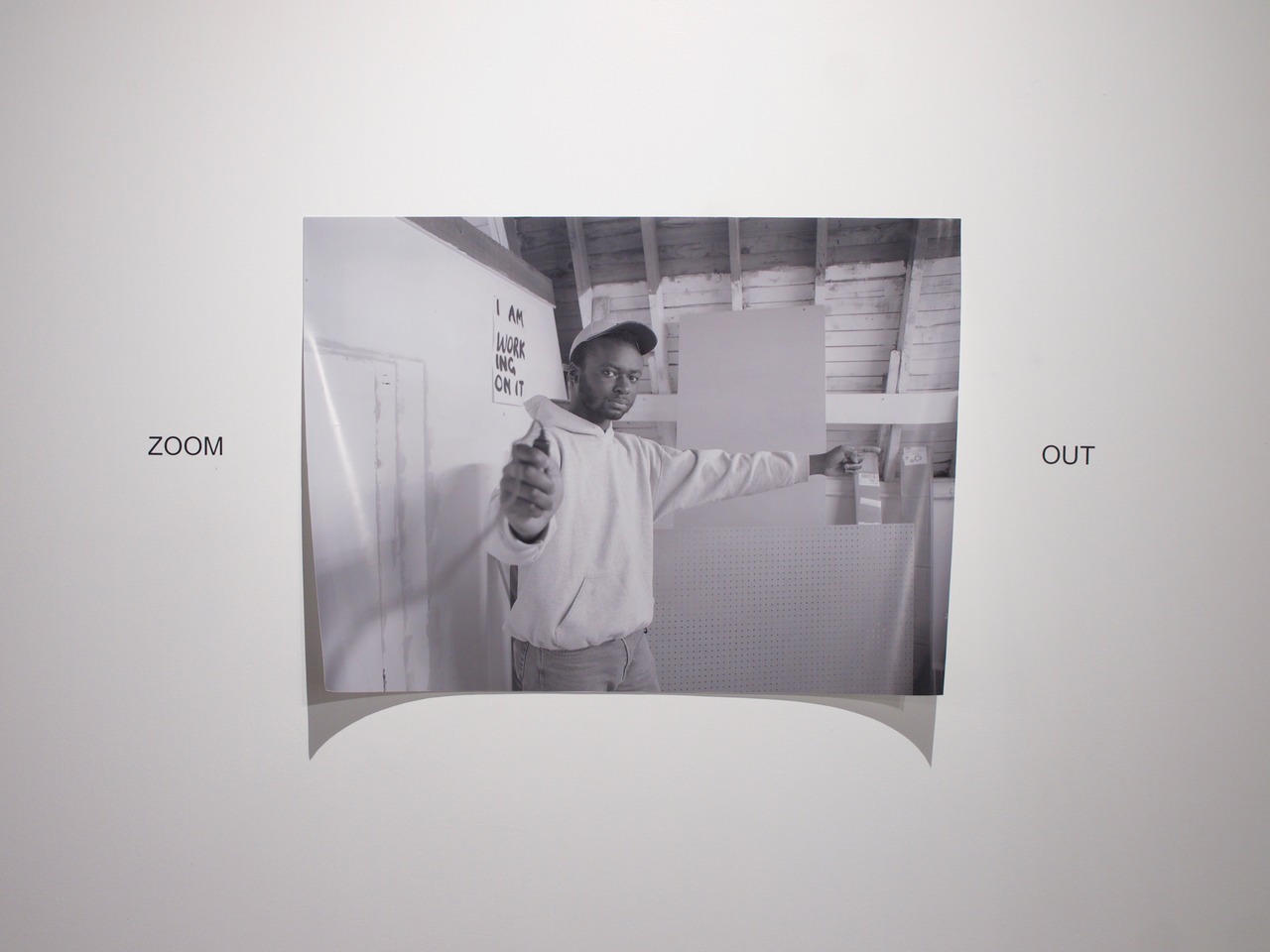

Latitude 53 is pleased to welcome Winnipeg based artist, Luther Konadu. Konadu’s work Figure As Index focuses on the way objective visual documentation ostensibly formulates public perception, particularly that which surrounds collective identities and historic record in relation to the black body. In his work Konadu observes that history has always been told by its victors, making our understanding of the past limited and one sided. Using the tradition and legacy of documentary photography Konadu creates an alternate past to imagine a different future of self—as it relates to a social communal context.

Dear Luther,

I am writing to you in the wake of the deeply troubling acquittal of Gerald Stanley from the murder of Colten Boushie. I sit in dumb shock while my social networks are in uproar—online and in real life—demanding justice for the 22-year old Indigenous man’s murder at the hands of the white Saskatchewan farmer. As a response to this acquittal and the larger monster of systemic racism it brings to light, people have begun circulating images of the smiling young man with the banner, “Justice for Colten.” The most popular ones are animated and colourful duplications of the original photo, which I’m sure was taken by a friend or a family member, somebody whose warm gaze encouraged that smile. Have you seen these images, Luther? Have you saved some of them to your growing Instagram collection?

Nobody in your portraits is ever smiling, not even you. The subjects follow your strict set of rules by holding a neutral face, not wearing any visible logos—and always looking at the camera. Without their fashion betraying them, they seem to be (briefly) lifted out of present time. They become emblematic of what you’ve identified as the broader issues of representation that have marked racialized bodies since colonial time. You reference instances as far back as the 19th century when black bodies like yours and brown bodies like mine were photographed in our native habitats—captured and frozen in time—to travel back to the colonial centre as postcard-sized proofs of cultural and racial difference. Not much has changed from those records to the archive of the present where we are presented with neo-colonial projects of National Geographic, mugshot photography, and video surveillance culture that have taken on the task of narrating our bodies into public existence.

Culled from such archives, your subjects are depicted in ways that make it possible for the viewer to sift through the amalgamation of histories that inform the photographic surface. One of the works that immediately comes to mind is the diptych where you’ve coupled a self-portrait of yourself standing with one that is seated. In the first scene, you positioned yourself in a cool contrapposto (not unlike Michelangelo’s David), and in your second you hold our gaze even as your body slumps down in the chair. All the while the cord for the self-timer snakes around your fingers as a signal of your control in the production of this image. You are authoring the ways in which your body will be framed for our reading. In other works, you continue to resist the singularity and objectivity performed by colonial images of racialized subjects by constructing a circular 360-degree world around them. There are diptychs, triptychs, polyptychs, slews of poetic text, and now your newly erected Truth Study Center, whose scattering of images with visual and textual references further breaks apart the singularity of the image.1 Thinking through the history-making potential of photography, Peter Friedl has written, “To capture death, you need the right technique and the right moment.”2 If we replace the action of capturing “death” to one that affirms the “life”, “nuance”, and “complexity” of individuals from our various communities, I feel that your exploratory and expansive photographic practice is, similarly, engaged in writing and righting history.

Luther, as you record the minutiae of shifts in postures—the briefest of which is a slight raise in the eyebrows and the most dramatic a complete frustration of the borders of the photographic frame—you are reaching like a foghorn out the of the depths of enacted and reenacted colonial hell that has endeavored to consume bodies like yours, bodies like mine, bodies like Boushie’s. In the end, it is your gaze, your circular movement, and your refusal to be pinned down that articulates our future: the right to life and self-determination.

Noor Bhangu

Noor Bhangu is an emerging curator and writer living in Winnipeg. Her upcoming projects include Wrestling with Angels: Artists Revisit the Canon(s) and womenofcolour@soagallery.

Konadu’s Truth Study Center is based on Wolfgang Tillmans’ ongoing project of the same name, which plays on the search of finding objective truth in our post-truth world.

Peter Friedl, “History in the Making”, E-flux, September 2010. Accessed 13 February, 2018. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/18/67426/history-in-the-making/.